Spotlight on the Relationship Bill of Rights

The history of, and a new approach to, ethics in polyamorous relationships

This blog post is part of a series on the new, vastly expanded More Than Two site. This essay spotlights the Relationship Bill of Rights page. Look for more spotlights in the coming days and weeks!

Way way back in the early 2000s, I published a “Secondary’s Bill of Rights” on the More Than Two polyamory site. Overnight, it became the most-visited page on the sight by far, and also generated the most email of anything I’d ever put on the Web.

Image: grechka33

It can be hard to remember this, in 2024, as we look back on the way things once were in the Before Times. An entire generation has passed since I put up the Secondary’s Bill of Rights. A lot of folks today won’t remember this, but it once was the case that “primary/secondary”—the idea that polyamory was something a (usually married) couple did, opening their relationships to new partners under the strict condition that the couple came first and could end those secondary relationships at a moment’s notice—was the dominant relationship model.

In fact, that’s how I started out, back in the 1980s. The word “polyamory” wasn’t in circulation back then, so my first wife and I called ourselves “open.” We began our relationship in what would today be called a “polyamorous quad”—I started dating my ex-wife 24 hours almost to the minute before another woman asked me out, a woman who would later go on to date my best friend. My ex-wife quite fancied my best friend, and had considered asking him out before we went on our first date. So yadda yadda yadda, she and my best friend became lovers, and his girlfriend and I became...well, not lovers exactly, but more like snogging friends. (My ex-wife and my best friend would go on to be lovers for...hmm. Eight or ten years, I think? I don’t recall exactly.)

Anyway, through all that, and through my ex-wife’s other relationships and my other relationships, we very much had the idea that we were The Couple™, and could always veto one another’s relationships for any reason or none. I never used that veto power myself, though my ex-wife vetoed a couple of my relationships, even going so far as to say that I was forbidden to remain friends with or even speak to one of my former partners.

It’s hard to believe nowadays, but that sort of thing was common as polyamory got its start.

Polyamory as Org Chart

Image: vichie81

As weird as this sounds today, polyamorous relationships once frequently looked like corporate org charts, with the primary partner on top and secondary partners beneath. Secondaries were frequently treated as though they should be grateful to have whatever they got, and if they didn’t like it, hey, they could find a primary of their own, right?

There were a lot of historical reasons this approach was so common, back in the day. We were all exploring largely uncharted territory; multiple sexual partners were nothing new, of course—the swinging scene had been around for ages, and various forms of non-monogamy have existed at least as long as we’ve been recognizably human—but multiple romantic relationships? C’mon! That way madness lies. What was there to keep you from constantly shagging all and sundry, continually trading up to better and better partners? Only strong rules could prevent the inevitable slide into chaos that all of Western society warned lay at the end of this road.

The idea that a secondary partner had rights, that a secondary should be treated as anything other than fully subordinate to the primary—now that was a dangerous idea.

A lot of the email I got from the Secondary’s Bill of Rights...wasn’t exactly a glowing endorsement. Primary/secondary hierarchy was, at least to a lot of folks, the only thing that separated polyamory from a complete degenerate free-for-all in which nothing was stable and nobody was safe.

Fast forward fifteen years, and things have changed enough that the idea of “secondary’s rights” no longer seemed quite so threatening. I started getting more emails, this time with a different spin: “Why do you call these ‘secondary’s rights?’ Shouldn’t everyone have these rights?”

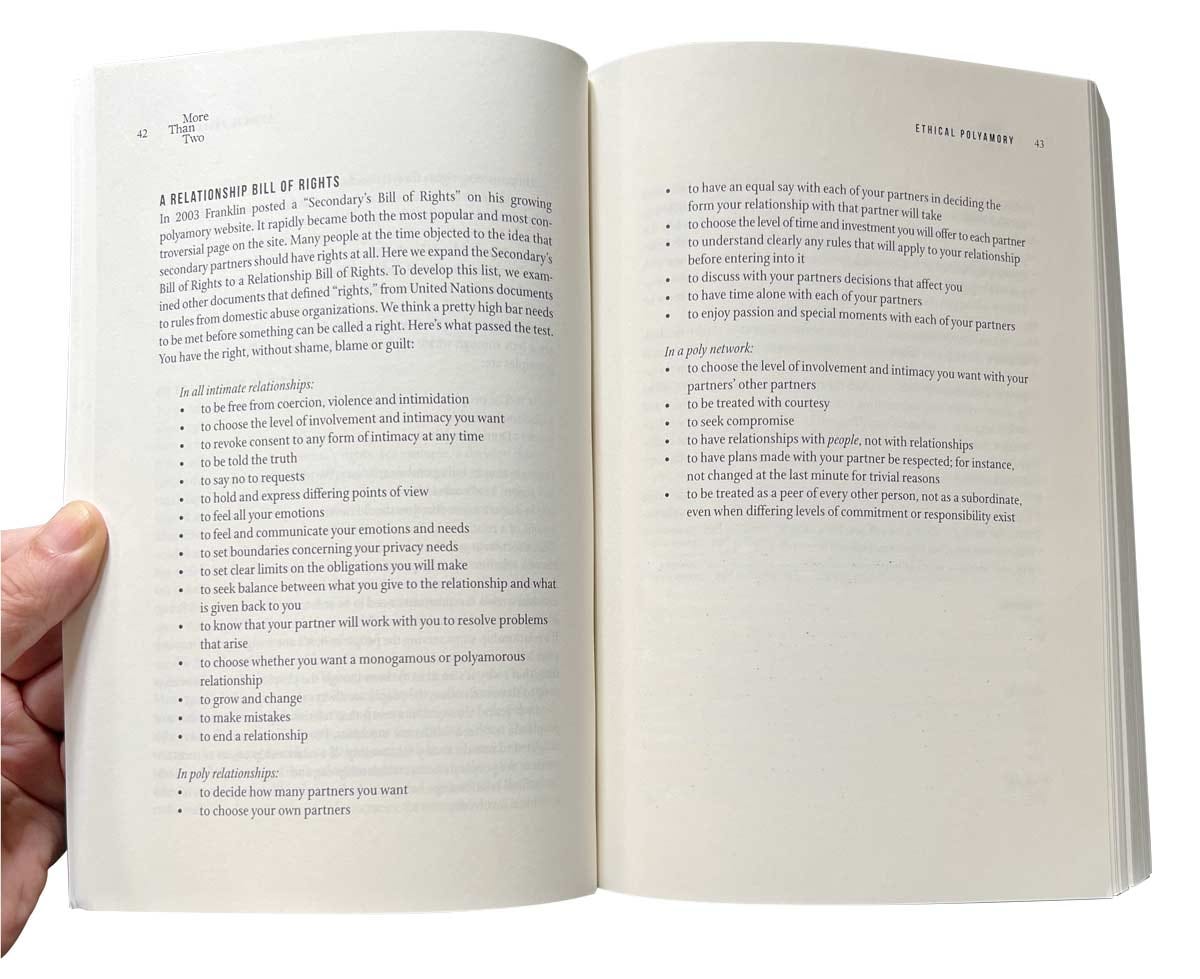

When I sat down to co-author the book More Than Two, we took those emails to heart, and expanded the idea of the Secondary’s Bill of Rights into a Relationship Bill of Rights.

Alas, we didn’t really know what we were doing, and so what we wrote sounded good in theory, but didn’t really consider the many ways in practice that people in a relationship might mistreat one another.

Toward a More Informed Idea about Relationship Rights

When I started revising the More Than Two site, I wanted to revisit the idea of a “relationship bill of rights.” I wanted to get away from the idea of secondary’s rights vs primary’s rights, and also from the idea of polyamorous relationships rights vs monogamous relationship rights.

The result is the new Relationship Bill of Rights page on the relaunched site.

Now, I’m not saying this is perfect, not by a long shot. The conversation about ethics never stops. I am certain that I will revisit this in the future.

I think it’s an improvement over the first attempt in the More Than Two book, for a number of reasons, not the least of which is I no longer believe there are “rights you have in a relationship” and “rights you have in a polyamorous relationship.”

It’s also more informed, both by my own experiences with unhealthy partners going all the way back to my first wife that I am still unpacking through therapy, and through conversations with other people who’ve been at the receiving end of mistreatment by romantic partners.

Key to this new, more informed exploration of relationship rights is the idea that all rights originate from the wellspring of respect for human agency and autonomy, and that almost all forms of abuse are rooted in power and control. With this foundation, relationship rights are those things that protect agency, and violations of those rights are almost always about non-consensual exertion of power and control, directly or indirectly.

The Right to Say No

The contemporary conversation about consent is deeply flawed.

Image: Madalyn Cox

We hear the idea that no means no, but it sometimes doesn't sink in. Far too often, I see people who ostensibly claim to value consent—sometimes people who even give interviews about consent, present workshops about consent, write books about consent, claim to want to build a ”culture of consent”—who don’t, when the rubber meets the road, actually seem to know hat consent is.

Oh, they understand that you mustn’t do things that someone tells you not to do, don’t get me wrong.

The problem is that they see “I have to get them to say yes” as a checklist item, a tickybox on the road from where they are now to where they want to be. They hear “no” as something to be gotten past, over, around, or through.

“But why did you say no? What are your reasons?Oh, those reasons aren”t good enough. Have you considered...?” This is way too common, way too accepted (even within consent communities), and way too tolerated. I’ve had this happen to me—more than once!—and the thing is, it’s so common, so unremarkable, I didn’t even recognize it as a consent violation.

Consent does not mean getting someone to say yes. Consent means going forward only if that’s truly what the other person wants.

This idea—that respect for agency isn’t about changing someone’s no into a yes, but about truly respecting what other people do and don’t want—formed the starting point for the re-imagined Relationship Bill of Rights.

This still isn't the end of the conversation, of course. This stuff is hard, and even people with genuine good intent can and do miss things, get things wrong. I hope to return to this page as I learn more...and I hope I will never stop learning.